Yahweh – the God of the Bible – took six days to create the world and realizing that everything was good, he sanctified the Sabbath so that the good creation would be remembered: everything was placed in the right place, distinguishing by contrast – light from darkness, earth from water… – and finally leaving it to his favorite creature to give a name to each one. As if to say that at his first glance Jehovah God must not have looked at the darkness distinct from the light nor the sea separated from the earth – in the same way Art could not and did not know how to look differently from how the creator of all things turned his first glance at them to take stock – whether it was a good thing or something to be redone. So that creation, even if it happened on different days, did not imply that each created thing could be looked at separately. You cannot see the stars separated from the light nor can you hear the pouring of rain without seeing the clouds. In short, since it is a complete design, it must be looked at with a gaze that in its completeness can grasp its components – their implicit correlations that reveal their coherent harmony, the functionality of the correlations between things destined to interact in any case. And this must have been precisely the type of gaze that man must have given to creation in order to be able to give a name to each thing that Yahweh himself had from time to time recognized as good. And how could man invent the name to give to each thing he saw with his own biological eyes – having to confirm the Creator’s judgment that they were all good things? Good – for whom? Man’s gaze was certainly initially innocent – so much so that he observed the world in the same way that the Creator had considered the things he had just created; until the beloved creature emancipated himself from reason, managing to glimpse, well beyond the distinct things, the interweaving of their correlations. The spur of reflection allowed him to delve deeper into ideas that were immediately inventions – those expressed by the cavemen of Altamira, Lascaux, Chauvet. An energy – that of creativity – that is attributed to artists committed to producing works of which it can be said every time that it is a good thing.

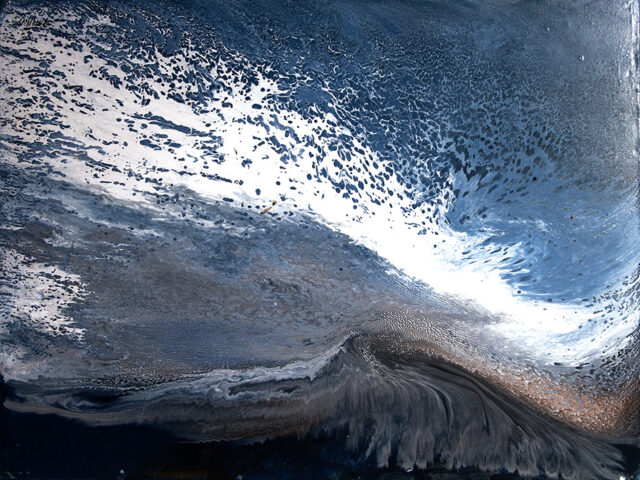

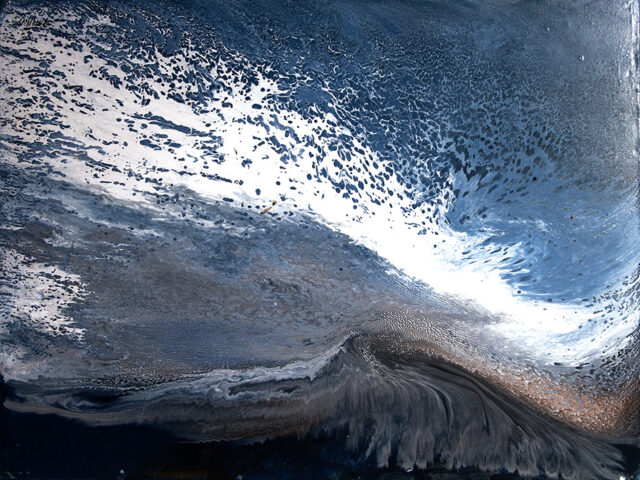

A gamble – to tell the truth – because the cold logic of reasoning does not always manage to make the numbers add up: how can the sea of Vincent Van Gogh be equally “a good thing” (which in Saintes Maries de la Mer leads him to go beyond color) which is completely different from that of William Turner who in storms interprets a sublime fatality signed by extreme chromatic expressiveness (think of the Shipwreck of 1805); not to mention the six shipwrecked people of Ivan Aivazovsky who in 1850 lets us glimpse, beyond the terrible ninth wave (the most powerful of the destructive sequence of storm surges), a light of majestic hope that rises above the waters.

For a symbolic representation of the force of a threatening wave, then – without insisting on refined naturalistic chromatisms –, we must refer to the “Great Wave of Kanagawa” (1831) by the Japanese Katsushika Hokusai. The simple phenomenon of the wave – to be contrasted with the ephemeral fragility of man – resorts to pictorial narratives that are however far from expressing the density of ancestral fears. Even if Paul Gauguin – by fusing the techniques of oriental art and condensing the introspective themes of his refined spirituality – manages to decline cloisonnism by delimiting the figures with marked contours that enclose contrasting colours (consider The Wave of 1888). The exhibition could develop by calling for other testimonies – from Claude Monet and Giovanni Fattori, for example, to Margherita Sarfatti. Artists who have described the sea in its various forms, in different seasons, at different times of the day… (think of the effort of the Macchiaioli committed to fixing the effects of the different intensities of light on the landscape; or the effects induced by the “Castiglioncello School” of the Sixties committed to perceiving the warm and reddish light that takes on tone when the hot winds blow to create those luministic effects that involve the natural elements of sober and solemn, bare and earthy landscapes.

Yahweh – the God of the Bible – took six days to create the world and realizing that everything was good, he sanctified the Sabbath so that the good creation would be remembered: everything was placed in the right place, distinguishing by contrast – light from darkness , earth from water… – and finally leaving it to his favorite creature to give a name to each one. As if to say that at his first glance Jehovah God must not have looked at the darkness distinct from the light nor the sea separated from the earth – in the same way Art could not and did not know how to look differently from how the creator of all things turned his first glance at them to take stock – whether it was a good thing or something to be redeemed. So that creation, even if it happened on different days, did not imply that each created thing could be looked at separately. You cannot see the stars separated from the light nor can you hear the pouring of rain without seeing the clouds. In short, since it is a complete design, it must be looked at with a gaze that in its completeness can grasp its components – their implicit correlations that reveal their coherent harmony, the functionality of the correlations between things destined to interact in any case. And this must have been precisely the type of gaze that man must have given to creation in order to be able to give a name to each thing that Yahweh himself had from time to time recognized as good. And how could man invent the name to give to each thing he saw with his own biological eyes – having to confirm the Creator's judgment that they were all good things? Good – for whom? Man's gaze was certainly initially innocent – so much so that he observed the world in the same way that the Creator had considered the things he had just created; until the beloved creature emancipated himself from reason, managing to glimpse, well beyond the distinct things, the interweaving of their correlations. The spur of reflection allowed him to delve deeper into ideas that were immediately inventions – those expressed by the cavemen of Altamira, Lascaux, Chauvet. An energy – that of creativity – that is attributed to artists committed to producing works of which it can be said every time that it is a good thing.

A gamble – to tell the truth – because the cold logic of reasoning does not always manage to make the numbers add up: how can the sea of Vincent Van Gogh be equally “a good thing” (which in Saintes Maries de la Mer leads him to go beyond color) which is completely different from that of William Turner who in storms interprets a sublime fatality signed by extreme chromatic expressiveness (think of the Shipwreck of 1805); not to mention the six shipwrecked people of Ivan Aivazovsky who in 1850 lets us glimpse, beyond the terrible ninth wave (the most powerful of the destructive sequence of storm surges), a light of majestic hope that rises above the waters.

For a symbolic representation of the force of a threatening wave, then – without insisting on refined naturalistic chromatisms –, we must refer to the “Great Wave of Kanagawa” (1831) by the Japanese Katsushika Hokusai. The simple phenomenon of the wave – to be contrasted with the ephemeral fragility of man – resorts to pictorial narratives that are however far from expressing the density of ancestral fears. Even if Paul Gauguin – by fusing the techniques of oriental art and condensing the introspective themes of his refined spirituality – manages to decline cloisonnism by delimiting the figures with marked contours that enclose contrasting colors (consider The Wave of 1888). The exhibition could develop by calling for other testimonies – from Claude Monet and Giovanni Fattori, for example, to Margherita Sarfatti. Artists who have described the sea in its various forms, in different seasons, at different times of the day… (think of the effort of the Macchiaioli committed to fixing the effects of the different intensities of light on the landscape; or the effects induced by the “Castiglioncello School” of the Sixties committed to perceiving the warm and reddish light that takes on tone when the hot winds blow to create those luministic effects that involve the natural elements of sober and solemn, bare and earthy landscapes.

di Vito Antonio D’Armento

Hot Pepper Taralli

Hot Pepper Taralli

Country Orecchiette

Country Orecchiette

Classic Taste Taralli EVO

Classic Taste Taralli EVO

Olio d'Oliva E.V. 500 cl.

Olio d'Oliva E.V. 500 cl.

Sciana

Sciana

Leave a comment